Bhutan: Oreos on the altar, phallic symbols on the doorposts.

By Melanie A. Katzman

Bhutan takes your breath away. In so many ways. The beauty! The altitude! It’s high up in the Himalayan foothills. Whether you’re walking or driving, there are few straight lines; instead, constant blind switchbacks, up and down the mountain with no guard rails, and deep valleys below.

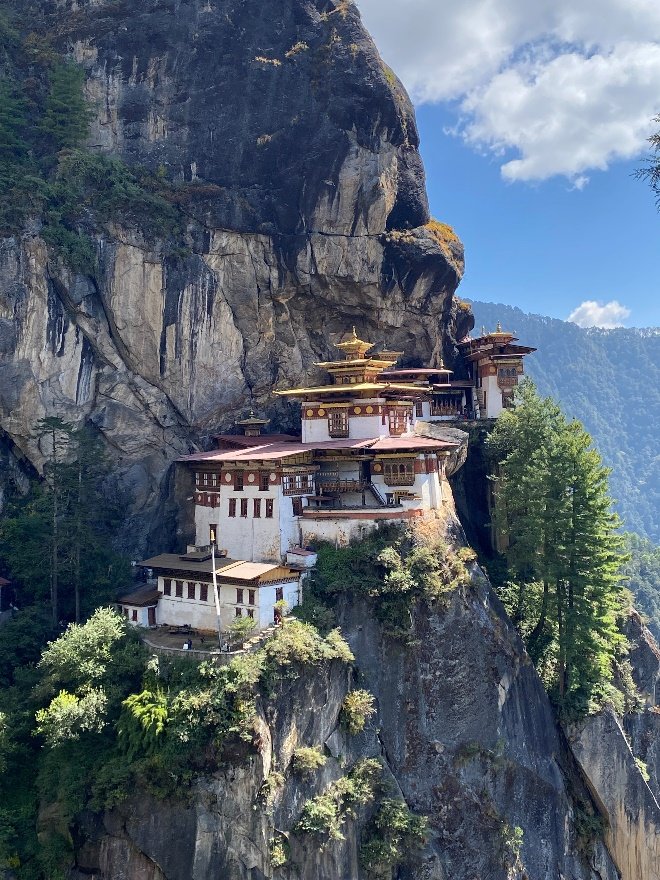

The rapid ascent and descent, the acute attention required, and the awareness of your breath, generate a meditative state that is fundamental to the Bhutanese experience. Everywhere you look you’ll see a temple teetering on a cliff, tempting you to join the many monks (and others) whose life’s focus is praying for peace.

The people of Bhutan, as well as the landscape, are embracing. Paro International Airport, the second highest airport in the world, sits in a short narrow valley. Pilots can’t fly using instruments— they can only land in daylight. And only when the sky is clear. There are mountains to the north, east, and west. There’s jungle to the south. Nature’s elements keep the Bhutanese in and the world out.

It’s not easy getting to this glorious country. The number of entry visas is controlled, and tourists pay a daily tax to support the country’s sustainability goals. Your efforts are clearly appreciated. As nestled as the terrain is, there’s also a sense of expansiveness. Whether we arrived at a fine hotel or a mountaintop tent camp, we were always greeted with a cup of tea. Why rush? Let’s get to know each other first. Then, the woman is offered the room key. Tradition! Property passes through matrilineal lines.

The country is one-third the size of Ohio with a population of 750,000. People live in quite remote places, which makes the nation’s goal of connecting everyone by (at least dirt) road and electric lines all the more ambitious. What’s really impressive is that it’s one road—no GPS required—just take off and keep turning. There are no traffic lights in the entire country. Remarkably, no car horns blow. The only real congestion is caused by cows and horses, and they get the right of way. Some of the roads are very rocky, and when we hit a particularly challenging patch, our driver, Kalpo, called out “car massage!” and somehow it went from uncomfortable to a bonus beauty treatment.

It’s so quiet. You hear crickets during the day. There’s no visual pollution. No brands making their pitch—no neon lights, no billboards. In town, store names are in Dzongkha (the national language) and English. I lost count of how many times I saw the words, “cum” and “karma” and “phallic.” One shop offered “Phallic Pilates, just come.” What are they teaching?

It’s a country that resisted missionary efforts to convert the populous with an anglicized Jesus herding sheep. The Bhutanese strain of tantric Buddhism with secret rituals, wrathful flaming deities, skulls, and phalluses is a better fit.

The country has a long history of devotion to charismatic leaders. The Buddha (aka “First Lord Buddha”), the Second Lord Buddha, and the Great Unifier (who brought the five valleys of Bhutan together into one country). Tributes to them fill every temple; their images differentiated by the amount of facial hair, none, a mustache, and a flowing beard, accordingly.

In addition to these larger-than-life characters are countless spirits called “Naga” which are part of Bon, an ancient animistic religion that teaches respect for the earth and all sentient beings. Naga are susceptible to pollution; if you spoil your environment, the Naga will seek revenge. Remember that!

The Bhutanese combine the spiritual and the practical with a fair dollop of iconoclasm tossed in. Even the last king, Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, questioned his own abilities to modernize the nation and forced democracy on the people. However, loyalty persists. The Bhutanese have an election approaching next month. We saw no campaign posters. Instead, we witnessed people wearing buttons with photos of the royal family members. The smiling, regal faces are framed decor for temples, restaurants, and homes.

Disruption. Balance. Challenge. Compliance. The coexistence fascinated my dualistic western mind.

The power of the flaming thunderbolt is still taken seriously. It symbolizes the discomfort society experiences when facing truth. In the 15th Century, Drukpa Kunley, known as the “Divine Madman,” shot fire from his penis and destroyed the demons that ruined crops and made some women barren. So what if he slept around, defecated everywhere, and drank too much wine? He challenged social norms and made clear that sins of the flesh are probably the least destructive to humankind when stacked against anger, jealousy, greed, and pride.

Near the town of Punakha is Chimi Lhakhang, the fertility temple. Walking through the valley, we were surrounded by shops selling all kinds of phallic art, even kids’ crayons in the shape of penises. An adolescent dream. Once at the temple we learned about the conception rituals, which include women being anointed on the head with a large wooden phallus. The impact of Drukpa Kunley carries on. If you meet a Bhutanese named Kunley, it’s a good chance their folks were honoring the effectiveness of the prayer penis.

There’s a delightful interplay between the extreme respect for religious deities and leaders (dead and alive) and the playful feeling one experiences when entering temples. The buildings are often quite bland on the outside yet explode with jellybean-colored iconography on the inside. And the gold. So much gold. And so many Buddhas. And Oreos—on the altar along with Himalayan scotch bottles. Deducing from the offerings, the gods are having a wild time.

And so are the locals. We joined the Jakar Tshechu festival at the Dzong in Bumthang. Dancing monks donned masks to amuse the audience and also desensitize them to the creatures they might meet upon death. Life, death, reincarnation. The cycle is woven into daily life. Impermanence isn’t questioned.

There are 19 Dzongs throughout Bhutan. Traditionally they were used as fortresses when warring tribes and the Tibetans invaded. Now they are religious centers. Collections of weapons and armor sit side by side with golden Buddhas capturing the continual juxtaposition of opposites that infuses the culture. You’re not allowed to photograph in the temples, which is a great way to ensure that you savor the images and commit them to your mind’s eye.

And did I mention butter? Temple candles are made from butter. There are multiple butter lamps in each holy place. And the tea we drank with all our new pals was made with butter (and salt). Those cows are put to good use. There’s lots of cheese in many of the dishes. My favorite was “ema datse” or chili cheese. The chilies are ubiquitous. Corrugated metal rooftops are blanketed by red chilis that leave their blush stain creating a pointillistic painting against the ever-present, lush, rolling green hills.

Red is an awesome contrast color. It’s also the color worn by monks. Thousands of Bhutanese become monks and thousands become tour guides. As a result, it’s not unusual for a family to have a child who’s guiding our souls while the other is arranging our dinners.

Bhutanese meals have lots of little bowls of vegetables, chili cheese, chili mushrooms, rice with a side of chili paste, and sometimes a protein cooked with peppers. Small slices of apple or banana complete your repast. Local manners dictate that as soon as you finish, the table is cleared. It’s the only thing that feels rushed in Bhutan. Pro tip: leave some food on your plate and you get to linger.

Staying in farmhouses and guest houses, we were invited into the kitchen. I learned how to make “mo mo” or dumplings. And of course, chili cheese. I couldn’t find a solely Bhutanese restaurant in NYC. I sense an opportunity.

Wherever we went the Bhutanese hospitality was profound. I have countless pictures of “new family.” At the fancy hotels they offered us oxygen upon arrival (we declined) and suggested they do our laundry (we gladly accepted). They gave us hot water bottles before bed (it’s cold at night). After a day of trekking, our camp site didn’t offer oxygen (wish they did) but they also provided hot water bottles along with plastic clogs and a lantern to make the midnight jaunt to the outhouse more pleasant. The wild horses sleeping alongside us and the dogs that adopted us as we panted up the hills added to the charm.

Trekking at 13,000 feet isn’t easy but it’s totally worth the black toes and sore calves to be able to wake up above the clouds, watching the sun illuminate the mountain peaks, and then walk down to the iconic Tiger’s Nest. Clinging to the mountainside, the beauty of this amazing temple doesn’t disappoint. Throughout my travels, I seldom saw foreigners; however, a few hours at Tiger’s Nest more than filled our quota.

Most visitors are accompanied by guides, and all guides and most locals when visiting public places must wear customary attire—a full length “Kira” for women, and a shorter “Gho” for men. The color of one’s large, cuffed sleeve reflects your position in society. The Gho crosses in front like a bathrobe, excess fabric is gathered at the waist and tied with a belt. The wrapping creates a special pocket where, among other things, cell phones are stashed. Again, tradition and modernity weave (almost) seamlessly together.

Over the course of our time in Bhutan, our guide, TG, changed into sandals while we rafted and hiking boots while we trekked. But his Gho, and the Gho of every guide we saw, was neatly pressed. We were hot, then freezing, and yet that Gho always seemed to keep TG in a temperature-controlled microclimate.

The homogeneity of dress, the stunning but recurrent mountain/valley motif, and the requirement that all buildings have the same trefoil (three-arched) window pattern, at times, made me question: Am I actually visiting a stage set?

Calming. Relaxing. And maybe a touch claustrophobic. And here lies the challenge.

One of the reasons I’ve long wanted to visit Bhutan was to better understand its Gross National Happiness index. About forty years ago, then king Jigme Singye Wangchuck said in an interview he would rather have a GNH rating than measure Gross National Product. What may have begun as a glib remark has resulted in a non-economic metric based on four pillars: Environmental protection, good governance, culture, and tradition. How does one of the world’s least-developed countries compete? By changing the definition of success. The Bhutanese have forgone opportunities to profit from their considerable natural resources in favor of quality of life. It does sell hydro power to India, but the excess water is replenished each monsoon season. Every couple of years citizens complete a happiness survey. The government’s goal is to ameliorate reported stress.

Do people answer the questionnaire honestly, given that it’s not anonymous? Is the plan to achieve national happiness working? I found myself cheering for the concept and worrying. In conversations with our local hosts, and over coffee with the former prime minister, Tshering Tobgay, I heard about Bhutan’s existential crisis. In a country of less than a million people, their population is dwindling. It’s dire.

Young people are leaving for training and jobs, mostly in Australia. Couples are having only 1.7 kids. They’re focusing on advancing careers rather than building families. Free education and health care aren’t compelling enough.

As I hiked through the serene Gangtey Valley in search of the auspicious black neck crane, whose seasonal arrival from Tibet had been noted just the day before, I imagined what others have thought and felt on this path as they pursued enlightenment. I asked TG.

He began with “La,” a term of respect that the locals use with each other and certainly with middle-aged folks like me. “La, we think about winning the U.S. visa lottery for a better life.” A little piece of me, crumpled. This coming from the devout man who spun every prayer wheel as we entered a place of worship, who knelt before the Buddha. TG wanted out of this bucolic land? He expanded, “Of course our desires are limitless.”

Oh my.

Tshering and I sit on the same business school board in Brazil. He’s very psychological in his approach as he runs for a second term as Prime Minister. What people need, he says, is a strong send of identity, security, purpose, and joy at work. I couldn’t agree more! They may also desire more “things,” but I didn’t press the point.

We shared some good laughs as he perused the table of contents of my book “Connect First: 52 Ways to Ignite Success, Meaning, and Joy at Work.” Tshering suggested I open an office in Bhutan. I’m thinking the commute from Manhattan’s Upper Westside might be a bit much. Especially on cloudy days.

I hope I do get back to Bhutan again soon. It’s like no other place I have visited. It’s traditional and progressive, it’s stuck in time and before its time. Prayer flags and mini stupas adorn the road, along with groups of 108 white flags to commentate those who’ve passed. They’re placed where there’s a breeze to help send the prayers to heaven. The flapping ribbons are a constant reminder to stop and reflect. To remember where we came from and where we are going—to think about what truly will make us happy.

"Happiness is the concern of everyone," says His Eminence Khedrupchen Rinpoche, the Fifth Reincarnate and head of the Sangchen Ogyen Tsuklag Monastery in Trongsa. He encourages us to "live life in the present moment. Happiness is not a by-product of external factors, but the result of positively conditioning your mind. Happiness is at the grasp of everyone." Who can argue with that?