Enter Confucius—He’s Back in Style

By Melanie A. Katzman

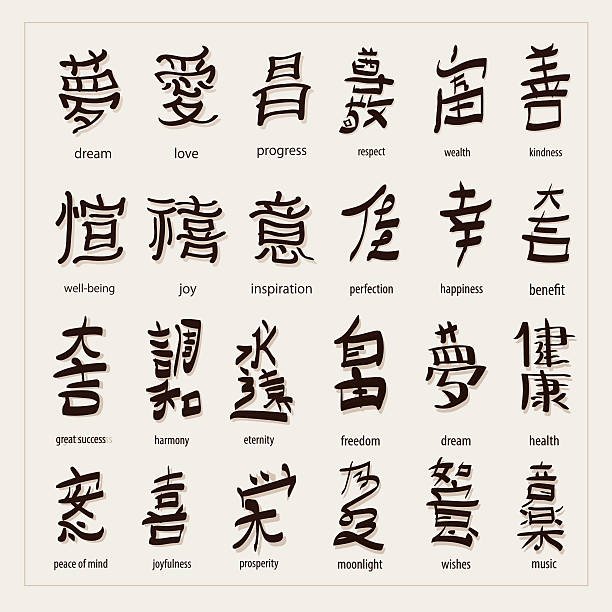

In four days and five nights I had a chance to reacquaint myself with China, which continues to provide deep brain stimulation every time I try to decode its intricate layers of history, hidden jokes, and enduring poetry. I am now even more fully convinced that the Chinese brain functions differently as a result of communicating in a language that is based on pictures as well as sounds and creates a playground for the development of both right and left brain functioning. To “make meaning” one has to work harder, stop and pay attention, and appreciate context. I found myself returning to my room at night to read MRI studies which indeed demonstrate that speaking English stimulates only the left brain, while Mandarin fires both hemispheres. What this neurobiological difference generates in perception must contribute to the problems in communication between East and West. It’s not just language, it is how one truly thinks about the world.

The Chinese aren’t being shady or indecisive when they say, “it depends.” It’s more like reading the Talmud where the answer to a direct question is “who’s asking?” This is a culture that doesn’t see “no” as a final answer, and as someone who always sees a “no” as a rest stop on the way to “yes,” I can relate. I have noted before that in China there is illegal, legal, and between the laws. Add to that the other axiom in China, “You can’t enforce every law.” This practical response was offered when we questioned why some regulations are merely aspirational. For example, the streets have graffiti numbers advertising for illegal licenses. When we asked, “Why don’t the police call those numbers and arrest the vendors?” the response is “Why? — it’s not really an offense that matters and you can’t stop it.” There are blogs and social media expressions of oppositional opinions. You can’t get onto Facebook or Google with a Chinese internet connection, but of course there are those international VPN’s…

The government appreciates that the days of total control are over; that Chinese people must be allowed to exercise personal freedom, but “to a point.” We have even seen how some of our more courageous hosts who have in the past been punished for their outspoken views are now being offered radio shows and trips to the States to illustrate the new China. Okay, maybe there’s some manipulation in there, but it’s a mutual dance. One request we hear is for the West to stop making human rights demands that attempt to force an overt withdrawal of control and could promote unrest. In China, it’s more about extending privilege without a fuss. Go too far and there are consequences. “Obvious” isn’t always better, and the value on subtlety comes up over and over again. This is not a country where one is offered answers, you need to know to ask. And it’s not a place where the answer is obvious — it often “depends” (see above).

Yet, not getting it right can result in shame or punishment, so you best watch for cues. As Westerners we don’t know the cues, move fast and seldom ask. Time and again my work with multinational companies illustrates how hard it is for an organization to accept that in China the CEO is not the decision maker, it’s the party leader. How many joint ventures fail because executives ask China to conform to their ways rather than seeing that both need each other? In one day of meetings, I managed to be with migrant workers, government officials, students, entrepreneurs, and a rare government-approved family therapy specialist running a pilot program to improve societal values by restoring competency and control at the family level. The topic of the group I led was, “Changing social structures and the impact on Chinese psychology” — made for me or what? And how great that I had so many executives who wanted to explore these issues, especially as they are in the business of selling luxury and potential pollution.

When working in China following the Arab Spring, there was a fear of a Jasmine Spring.

Protest by students is not the current concern, they are “too happy.” The fear now relates to migrant workers (defined as those moving to urban centers from impoverished rural areas). It is often described as an apartheid system as these workers can’t register for the same services (housing, education) as those in the cities. Expect to be hearing more and more about Hukous (or household registration, which migrants are currently denied).

There is great reliance on the migrant worker and the government encourages movement to the city as it’s easier to care for its public when all are living closer together. How to do this and also control crowding, pollution, and the inevitable separation from family is a great worry. Many countries are concerned about the social threat posed by growing income disparity – during this trip I was reminded about the Chinese twist. You may have heard me speak before about the beauty in walking through a Chinese park and watching the city wake up. People (especially the elderly) are ball room dancing, singing, and painting. On Wednesday, I once again saw a spontaneous band of retirees performing what sounded like love songs. They were actually ballads from the Mao era — essentially love songs to him — propaganda from an earlier period. There are those who long for the days when people were poor, equal, and happy. Mao did after all put “a chicken in every pot,” and ended poverty on a scale no others have achieved. The poor in China have food, and they are literate, and if you go to the countryside, you can see Mao’s picture framed on their dressers and you sense the quality of the simpler life. Historically, education was for the betterment of society, now it’s the means to wealth and the rush to accumulate is excessive. Shopping is as much a consumptive disorder in China as drinking. Despite the new toys and flowing scotch (Glenfiddich 15-year-old is everywhere), the realization that money can’t buy happiness is becoming clearer and clearer to this next generation that has grown up without a spiritual connection (post-cultural revolution), without siblings (thank you one-child policy), and often with parents who have suffered during the Cultural Revolution but cannot and will not put words to their experiences (and text books have erased this period so when you ask those most impacted by its aftermath they don’t really know what you’re talking about). Our interpreters (around 22-years-old) search for answers to what happened in 1966-1976. Those who left the country and came back have some clues. It’s like going to the Mandela museum in South Africa with locals: “What, this happened in my backyard?”

It was deeply interesting to lead a team of German executives who spoke to the Chinese about how a nation deals with the memories and recovery from social trauma that flourished from, and created, extreme distrust between people and ultimately irreversible cruelty. The 25th anniversary of Tiananmen Square is not acknowledged, so you meet people who have multiple layers of repressed (or denied) memory who have been raised by people whose traumatic experiences have not been validated. No wonder there is a search to “buy” an identity. Brands. Labels. Everywhere! Big chrome and glass malls with the same stores over and over again – Gucci, Dior, etc.

What’s different on this visit? The government (which is often quite wise) realizes they have a society in crisis. Who is “raising” the family? The government no longer regulates behavior like it once did; the multinational companies don’t provide the social structures once offered by state-owned enterprise. Thirty-five years into the one-child policy you have single children born of single children who singularly have to care for multiple elderly family members, often while living far away from their nuclear family.

Enter Confucius—He’s back in style. You will see more references to his principles of piety as the government hopes to help promote self-regulation after a very long stretch of government control of individual behavior. Recall, the Chinese are practical. They are also piloting marital therapy and parenting education to help couples stay together and more effectively create a healthy environment. We spent the afternoon with the professor who is running this pilot, and single children of single children can now have two children. More loosening to follow is expected.

When we asked young people what they wanted most in the future they often answered, “air and water.” You can see the air but not the sun (and you can appreciate why people wear masks on the street). It was so hot the pollution hung around your body, there was no way to feel clean and given the crowds and warmth and smog the desire to see sky feels urgent. Many rivers are openly polluted in contrast to the streets that are really not that dirty, though Beijing is even more crowded than before. Is it because it’s summer holiday? I don’t know, but it was at times unbearable, and I found myself saying, “I can’t wait to go back to New York City where the streets are roomy.” Kenzie (my Leaders’ Quest colleague, from Hong Kong) was disoriented by how much Beijing changed in the year since she was last there. More chain stores, more crowds, bigger buildings, and our little back-alley eateries closed. Kenzie and I have been working together in China for almost a decade. We have really seen the shift in density and “emptiness.”

And this being China, the emotional emptiness I explained before is now also quite physical given the new political leadership’s anti-corruption campaign. As the greatest social science laboratory, guess what happens when China turns the graft tap off? Where once we vied for an overpriced table at THE restaurants, now you can walk right in. The luxury brand stores don’t seem to have customers and once we left for Qufu, we found many, many half-built buildings. The big hotels offer Groupon deals for tea, early dinners, and even rooms. Our cab driver told us that he can now afford to buy wine. Who would have thought that one way to close the income gap was to make all income legitimate? Of all the things I observed this week, the anti-corruption campaign seems to be the biggest driver of change.

Ever wonder why so many people in China are called, “doctor?” I found out that you can buy degrees. With the new anti-corruption policy, I wonder if people will have to give their fake diplomas back.

With all this talk of morals, how perfect it was that Kenzie and I went to the home of Confucius, Qufu. Hint: Qufu has not figured out how to “market” or recognize its legacy. Who knew? I thought I would be infused with a deeper understanding of Confucian ideals (and at least come home with some good quotes). It’s a delightful small town with three main sites: his home, his temple, and a massive graveyard with trees and many decedents of the great man. Curiously, when invaded during the revolution, Confucius’s grave revealed no buried body. And as a reward for reading this much, imagine that when people say “his” name in English it sounds like they keep talking about being confused and creating “confusion.” Hum … maybe that’s because Confucius wrote about filial piety but his dad tried to give him away because he was ugly and then died when he was 3. I asked Kenzie if perhaps the dude wrote about loyalty to one’s father because he had coped with abandonment and abuse by idealizing his dad. When I heard that Confucius lost his mom when he was 17, I said, “You mean an orphan taught the country about family?”

Kenzie did not know anyone who had written a psychobiography on the sage and was intrigued by my idea that all this wisdom was simply overcompensation for early attachment issues. Come to think of it, Kenzie’s quizzical look when I questioned Confucius’s roots mirrored the puzzled faces I saw when I asked kids about the Cultural Revolution. I figured I was onto something and tried to research my theory online. Turns out, even in Qufu, my inbox was being wiped (you can see things disappear); I couldn’t access Google, and Bing was limited in what sites it would open. Okay, so maybe it’s not that free yet. I will see what I can find out once back in America.

Given that we couldn’t get “answers” or wisdom, Kenzie and I decided to get matching (super cheap) pocketbooks. Yup, went to the birth place of free education and we went shopping. I hope that the government rollout of Confucius principles has a better effect on the larger population.

But what I really encourage anyone to do in Qufu is take fashion pictures. This town has the whackiest, proudest fashion I have seen yet. I am ready for an iPhone; I just couldn’t do a Bill Cunningham thing on the streets with my Blackberry. There was great care put into clothing combos that were childish but sexy, super-colored and often included matching oven mitts to ride one’s bike (after all tan hands are associated with farmers, not fashionistas). The food was great, the hotel called to offer massages like the old days, and nothing cost more than a few dollars. There are silly scooters driven by grown women dressed like Barbie with Barbie decals, electric trams, horses, more bikes than you can imagine, and just a general undiscovered aspect that was delightful.

It was a thought-provoking, full and fun adventure which even included a trip to a LEED platinum shopping mall which is decorated with sculptures from the developer’s private collection (yup, Chinese duality — sustainable excess). Kenzie and I even went to a calligraphy exhibit where I finally had a little start to my long-overdue education on “what the hell do those brush strokes mean?!” It turns out, a lot. And to figure it out, you have to do the puzzle. And the puzzle depends on your knowledge of the basic idioms most Chinese learn in grade school. Of course, most Westerners don’t even know they exist, let alone what the idioms are. Under Kenzie’s tutelage, I learned that everyday conversation is infused with reference to these poetic idioms, thus further illustrating just how differently Eastern and Western brains are trained because poems are not so direct, let alone easy to translate.

So I leave you with this new bit of learning. Why do the entrances of so many Chinese restaurants and homes have a mirror on the left, calligraphy in the center that says “longevity,” and an urn on the right? Did you guess that the word for mirror and the word for urn, when said together, sound like the word for contentment and peaceful? Add to that longevity and you have created a “sign,” a wish at your doorstep that those who enter will enjoy a long and peaceful stay.

China: Social project, giant puzzle. Never disappoints. There’s a saying that the more you visit China, the more you know what you don’t know. I second that.